Singing Nature’s Song

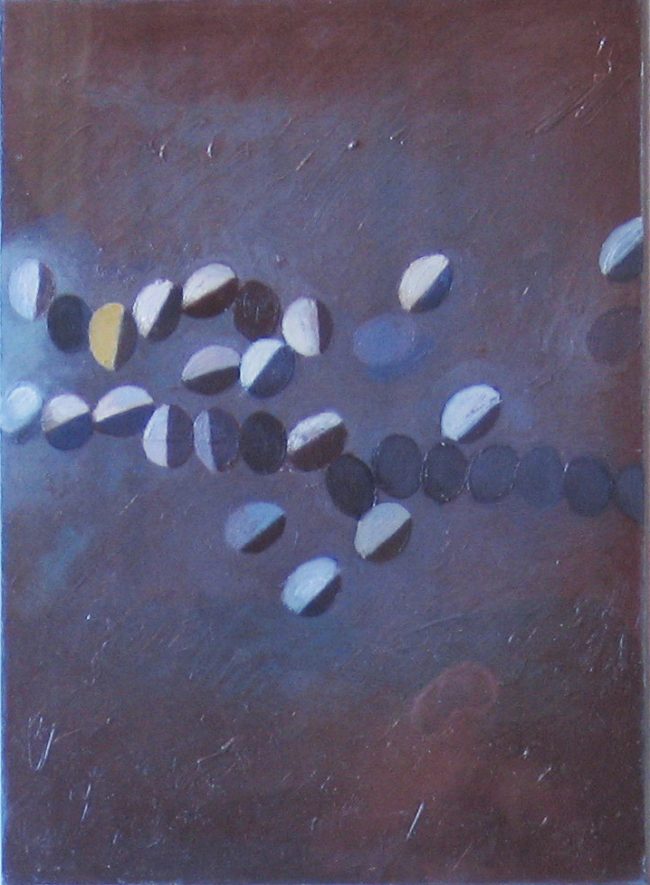

Dawn, 1976-80, Oil on hardboard, BGT852

Singing Nature’s Song

By Martin Kemp

I first encountered a group of Willie Barns-Graham’s paintings hanging together in 1982, when she was already in her seventieth year. Walking into the simple white space of the Crawford Centre in her native St. Andrews, I was captivated by their youthful joie de vivre (as it happens, the title of one of the present works). Their infectious freshness could have been that of a recently graduated student, launching new and varied works with untrammelled optimism into the public eye. Yet their apparently effortless mastery of different genres spoke of someone who had honed the art of picture-making over many years of mature questing. They spoke in a visual language that cannot be taught but can only be acquired by sustained empirical testing of how to make less do more, how to perfect the efficacy of the swift and the slow mark, how to tune the sounds of juxtaposed colours, how to energise the dynamics of shape across and within the plane of the picture, how to set porous opacity against veiling translucency, how thin sharpness and banded breadth converse with each other, and how a circle can swim, twist, float, sink and rise. They provided testimony to what Rowan James has nicely termed ‘a long lifetime of holding a brush’. Behind their spontaneity it was possible to sense the infallible scaffolding of nature’s living geometry – even at their most free – a structuring that has always served to articulate her pictorial intuitions. Willie’s works, then as now, are instinctive acts of pictorial breathing in harmony with the rhythmic pulse of the natural world.

Some observers, however admiring, have been puzzled by the apparent oscillations over the years between abstraction and representation, between orderly calculation and painterly spontaneity. Have we not been taught that an artist should have ‘a style’ and that the oeuvre should be seen to undergo ‘stylistic development’ from A to B? What are we to make of someone for whom A is possible again after moving to B, and that even C may occur in between? The clichés of critical and historical orthodoxy have never contained Willie’s creative variousness, and the set way of assessing an artist’s career is liable to miss the point of her ceaseless dialogue between sensed nature and the inner structures of cognition and memory.

Willie understands how acts of intense drawing or painting teach us to how to see as no other activities can. Sometimes, over the span of her career, she has relied on recognisable configurations of natural objects that act abstractly when rendered on the surface of the painting or drawing; at others, she has exploited the way that abstract shapes laid onto a flat plane can act as magical analogues for the spatial play of sensory experience in nature. Willie once said to me that drawing from nature keeps her ‘honest’. If I had been quick enough, I might have responded that her art was founded upon the two honesties necessary for anyone who aspires to be what Constable called a ‘natural painter’ – that of looking with the outer eye and that of seeking with inner eye.

On the surface, it seems that her modes of picture-making are firmly located in the later history of Modernism, particularly in the forging of nature-based abstraction in St. Ives in the 1940s and 50s. There are also clear and affinities with the rise of painterly abstraction in America during the 1950s and 60s. Indeed, it was around 1958 that the brushstroke began to assume a more prominent role in her picture-making, in a way that was analogous to what was happening in New York. Yet her irrepressible lyricism – however geometrically abstract the components of her composition – gave her a distinctive voice in the St. Ives context, and her refinement across a range of scales separated her from the assertive muscularity of Abstract Expressionism.

The recent works confirm the enduring character of her lyricism, always more sinewy than soft, which now finds expression in the ever fresher flowering of her colourism. It increasingly looks as if the deepest roots of this colourism reside less in St. Ives, where she has been such a key presence for almost sixty years, or in a response to the triumphalist developments in New York, than in her Scottish heritage. Any Scottish rootedness we may discern in her work is not be understood in the narrowly nationalist and often clichéed sense of Scottishness, but is to be characterised in terms of the historic internationalism that properly places Scottish Art in a European context. The wonderful eighteenth-century painter, Allan Ramsay, may serve in our present context as the supreme exemplar – a portraitist whose colouristic refinement, intellectual grace and humane insight speak of liaisons with French sensibility and an instinctive affinity with Italian classicism rather than with the imperial tenor of an English painter like Joshua Reynolds. It is only within Ramsay’s kind of broader cultural domain, if not in relation to Ramsay’s actual style, that Willie may be regarded as a Scottish artist.

The works in the current exhibition, originating from within the last three years, seem to be more consistent in mode than has often been the case, with the possible exception of Eclipse , in which the implicit geometry is granted explicit presence. Yet their titles signal that the range of resonance and reference is a great as ever. The advent of a title is never an orderly business for Willie, arising at various stages in the work’s evolution, sometimes only after its completion and sometimes not at all. Often the title serves to recall the scene that triggered the image, as a means of naming one in relation to another. However, even such mimetic names remain open to instinctive revision if they do not seem to do the right job. Above all, the title is never intended to circumscribe the ability of the picture to lead the spectator into varied realms of sensory and mental experience.

Without wishing to accord the act of titling an importance that it does not possess in Willie’s mind, I think we can see how the range of names given to her recent paintings does provide a suggestive clue to the evocative span of her artistry. Some of the titles apparently root the image firmly in seen nature. Night Garden and Island Eclipse, for example, suggest the particularity of a witnessed phenomenon, a poised moment in a special place, yet the pictorial elements refuse to be descriptive, and we may wonder if it is the act of picture-making that has brought about the eclipse and summoned up the colours that defy shadow. Perhaps the picture as it developed in her hands has converged upon our shared memory of nature rather than been literally extracted from the seen thing. Other titles seem to be more generally evocative, such as Carnival or Spanish Elegy, yet the pictorial repertoire does not appear readily distinguishable from the blankly labelled Untitled No. 11. Indeed the untitled and numbered picture contains one of those sketchily vibrant rings that we light be tempted to read in Dawn as the rising sun. Other of the titles, like Surprise, numbered 1 and 2, suggest her and our instinctive reaction to what the work has spontaneously become, while others seem to characterise the abstract nature of the composition. I am thinking of Green Flash or the two version of Inside Outside. By contrast, the Scorpio series, initiated in November 1997, takes its name from the star sign under which the first painting was conceived. The sheer variousness of titles in works of a comparable nature suggests that each could potentially be given any one of the types of caption. Perhaps most revealing are those that reach out beyond the contained realm of the purely visual – Singing Bird and, most notably, It Seems to Sing. The synaesthesic reference seems especially appropriate for works of such tuneful colourism and rhythmic joy. They exist in that paradoxical world of heard colours and seen sounds signalled by the cross-over vocabulary of art and music: ‘chromatic compositions’; ‘orchestral colour’; ‘tone’ (either musical and colouristic); ‘rhythm’; ‘harmony’; and so on.

Each work simultaneously begins from nature and ends in the picture and begins in the picture and ends in nature. If there is a close historical antecedent it is in those late works of Turner that he called ‘colour beginnings’ – works comprised of floating veils of paint which are at once autonomous improvisations in colour on surfaces and resonant evocations of the spatial structures of hue and tone in nature. Willie, for her part, is providing ‘colour becomings’ that the spectator’s imagination and memory are invited to bring into being, each one as our individual experience shared with her. When she immerses herself in the flux of light, air, water and earth in Cornwall, when she inhales the fierce tones of a baked landscape on a volcanic Spanish island, when she feels deep into the visual structure of rock or ice, when she confronts the great chords of colour in a Perthshire landscape, when she contemplates the symphonies of green in the wooden garden around her house in Fife, she draws the essence of the experience so deeply into herself that it can be reconstituted as an analogue in paint on paper or canvas, without even beginning to serve as a direct transcription of what has been seen. It is wholly unclear to me how the substance of paint allows any artist to do this. Willie just shows that it can be done, and how it should be done.

This article was originally written for the exhibition catalogue Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: New Paintings, published by Art First, London, in 1999