Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: A Scottish artist in St Ives

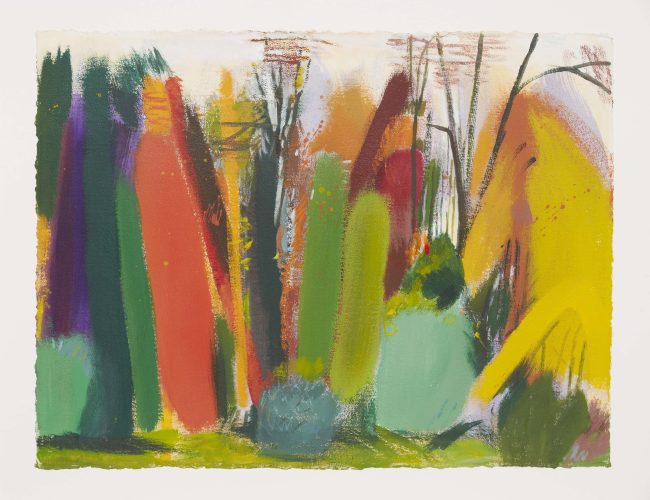

Autumn Series No.4 Balmungo, 1998, Acrylic on paper, 57.9 x 75.6 cm, BGT3019

Review of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: a Scottish artist in St Ives

Edinburgh City Art Centre, 24 November 2012 to 17 February 2013

By Douglas Hall

Coruscating colour, deliberate design and judicious mis-en-scene, precision of line; all these attributes of a major painter can be seen at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh until 17 February. The show is an enlarged version of the one recently seen at The Fleming Collection in Mayfair (London). So who is this major painter?

The painter is Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, whose centenary year it is. She died in 2004, aged 91, leaving her house, Balmungo near St Andrews, her artistic and considerable other estate to create a foundation to promote her work and reputation and to found bursaries for students of art. She was awarded a CBE and four honorary doctorates. She is represented in leading public and private collections and is the subject of two monographs. With all this honour, why begin this review in anonymity? The answer is that Barns-Graham has not yet received the public recognition, critical esteem and proper valuation that her status and outstanding merit deserve. The reasons are embedded in her life history and can only be hinted at here.

“What’s in a name?” Where status in the art world is concerned, a great deal. The name Wilhelmina Barns-Graham did its owner no favours in her long career as an artist. In her native Scotland, it instantly denoted her gentry origin, and her generation. In St Ives, where she spent her middle years, it competed with the clipped English monikers of Terry, Roger, Peter and the other male artists who were creating that force in British art called the St Ives School. That she was dubbed Willie was little help, though she answered to it all her life, and for brevity that’s what we will call her now. If her name was against her, so was her gender. As we have learned since the 1950s, to be a woman meant to fight still harder for recognition and due esteem. One woman at St Ives had done so with success. This was Barbara Hepworth, and there was no room for another.

Willie Barns-Graham, born in 1912, showed great early promise and seemed destined to be an artist. Her father, who was indeed a landed gentleman with estates in West Stirlingshire and Fife, did his best to prevent her going to art school. Fortunately, her aunt took her part, and she enrolled at Edinburgh College of Art in 1932. In youth her health was delicate and her progress through the College, often interrupted, was to last until 1939. But she was a star pupil, won prizes and was awarded travel bursaries which took her to Paris and the south of France. By this time, the attitude of the College to modernism was more relaxed, but not its devotion to teaching the basic skills of an all-round artist. This training, added to the riper sense of maturity that her background engendered, made sure that Willie’s progress to modernism would be evolutionary not revolutionary. Those attributes referred to at the start of this review were first imparted by Edinburgh College of Art.

Willie’s final year at the College ended in the fear and confusion of impending war. It was the enlightened Principal, Hubert Wellington, who suggested that she should go to St Ives in Cornwall, a safe and healthy place where, he knew, several interesting modern artists had already settled. He reckoned that Willie would soon make contact with them. She arrived in St Ives in 1940, and Wellington was proved right. Within months she had met a number of people who were already, or would become, luminaries of the art world. As to those who ‘influenced’ her work, the chief was Ben Nicholson. As Lynne Green points out, Willie did not arrive at St Ives as a blank canvas. The fact that Nicholson possessed similar attributes to her own, in his analytical precision of line and his infallible sense of balance and design, made him a senior partner to her, rather than someone to be imitated.

Although Ben Nicholson was the foremost exponent in Britain of abstract painting, it was not until the 1950s that St Ives began to earn its just reputation as the home of ‘advanced’ (i.e. abstract) English art. Willie’s work in St Ives and elsewhere in the 1940s is well represented in the exhibition. It shows her precision and perfect sense of balance and shapes but does not move into abstraction. The question of who among the St Ives artists first took that decisive step, and could claim to be an historic innovator, has provoked endless debate and partisanship. It was a principal cause of Willie’s relegation to a supporting role, a critical injustice that has dogged her reputation to the present day. But it is possible to see some reason beyond the mean-spirited sexism or classism that have been alleged.

Even when she had herself turned to abstraction, Willie’s work was less assertive than the work of the St Ives men like Terry Frost or Roger Hilton, brimming with masculine competitive energy as it was. British taste in new painting in the post-war period, jolted already by the unveiling of the Ecole de Paris, was more roughly shaken by the arrival in the later 1950s of American Action-painting or Abstract Expressionism. The dealers and gallerists who supplied such market as there was in recent art, recovering from wartime paralysis, saw the way the wind was blowing. They detected a whiff of American devil-may-care enterprise in the St Ives men which they did not find in Barns-Graham. I believe it is this, rather than prejudice, that explains why she did not fully share in the reclame, London exposure and commercial success of the new St Ives school. This is not to suggest that the result was fair.

The exhibition under review is the perfect opportunity to bury this sterile question and the persistent prejudice that has gone with it and assess Willie’s whole work. Lynne Green, the exhibition curator and her biographer, has seized it to good advantage. The exhibition occupies two of the spacious floors of the City Art Centre, and is so planned that the dazzling late work is saved to the end. On entering there is almost the feel of a family occasion, with the art school works of the determined daughter so amply justifying her self-belief, while her penetrating drawing of her rigid father, jaw locked in frustrated determination, looks on. Some of these early drawings show how much deeper Willie’s perception was than the usual standards that the life-class, say, required. Her drawing of the male model from behind, half represented as ecorche, shows a kind of steely pity and awe amounting to expressionism. The early drawings are cleverly shown near some very much later ones, when she was drawing the structure of a Swiss glacier, one of her landmark subjects. These are rightly seen as probingly sculptural, but one at least is open to a strangely anthropoid, romantic interpretation. All of which goes to show that Willie was, at all times, ‘a deep one’.

In 1960 Willie Barns-Graham inherited from her aunt the country house, Balmungo, now the home of her Foundation. St Ives had been her home for twenty years, and she was not about to leave it. Despite their 700 miles distance apart, Willie divided her time between the two places. But from that time, she quite quickly re-established herself as a Scottish artist, and she received a new degree of welcome and recognition in Scotland. That may well have been a factor in her new persona as a free expressive abstractionist, that characterised her late work. She had had regular exhibitions in Edinburgh since 1959, but they now assumed a more heavyweight character, culminating in a retrospective of more than a hundred works in the same City Art Centre in 1989, for which the present reviewer wrote the introduction. At her age of 77, this was the first detailed analysis of her work to appear in print.

What can be said here of her late work? Its kinetic and chromatic energy must be seen to be appreciated. Yet the precision and the infallible sense of balance are never lost. There should be no doubt now of her high place in the hierarchy of both Scottish and British painting.

© Douglas Hall 2012