Adaptation, innovation, and collaboration: examining the studio materials of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham

James Wright is currently studying for a Master’s degree in Technical Art History at the University of Glasgow. As part of a placement for his degree course, James has been cataloguing ephemera held within the Trust’s archives. These documents, which include colour charts, product catalogues, and invoices, amongst other items, document much of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s career from the 1960s onwards through the lens of materiality.

Some examples of artist materials catalogues from the Archive

The Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust’s retention of a significant number of materials used within Barns-Graham’s practice offers us a unique insight into the work of one of Britain’s foremost modernist painters. Combined with a significant collection of archival documents, these materials portray an artist who stood at the vanguard of painting until her death in 2004. The continuous adoption of new materials and methods and a collaborative approach to artmaking show us that Barns-Graham was an innovator. This adaptation meant the artist’s practice continuously grew and expanded throughout her life.

Barns-Graham's Barnaloft Studio as it was left after she died, 2004. Photo: Bob Berry

Adaption

The 1950s and 60s were an era of continuous innovation concerning artist materials. Most notably, the introduction of commercially viable artist’s acrylics profoundly impacted the nature of painting during this period. These products differed from traditional mediums such as oil paint and gouache, providing artists with quick-drying, water-soluble paint that offered excellent light-fast properties whilst mitigating some of the toxicities associated with conventional oil painting, notably turpentine. Furthermore, additional layers of paint could be applied over dry paint without reactivating the underlying layers, which allowed for continuous modification and enhanced colour differentiation.

Early users of acrylic paints included many American Abstract expressionist artists, including revolutionary artists such as Morris Lewis, Helen Frankenthaler, and Mark Rothko. Some of the earliest producers of acrylic paint include Leonard Bocour’s Magna Acrylic Paint, 1949, and Permanent Pigment’s Liquitex Acrylic Paint, 1955. These painters’ quick adoption of the acrylic medium shows that it helped facilitate idiosyncratic methods of production, enabling spontaneity.

A selection of Cryla acrylic paint from the Trust's collection

Within the UK, acrylic paint steadily gained prominence throughout the 1960s and was adopted by the British pop art movement. It’s use in Britain was championed by artists such as David Hockney, Bridget Riley, and Peter Blake, amongst others. An early example of acrylic paint in the UK is Rowney’s Cryla Acrylic paints. Archival studio materials held by the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust include early examples of Cryla Acrylics, and Barns-Graham’s earliest work recorded as having included acrylic paint dates to 1964, the year after Cryla Acrylics were first introduced.

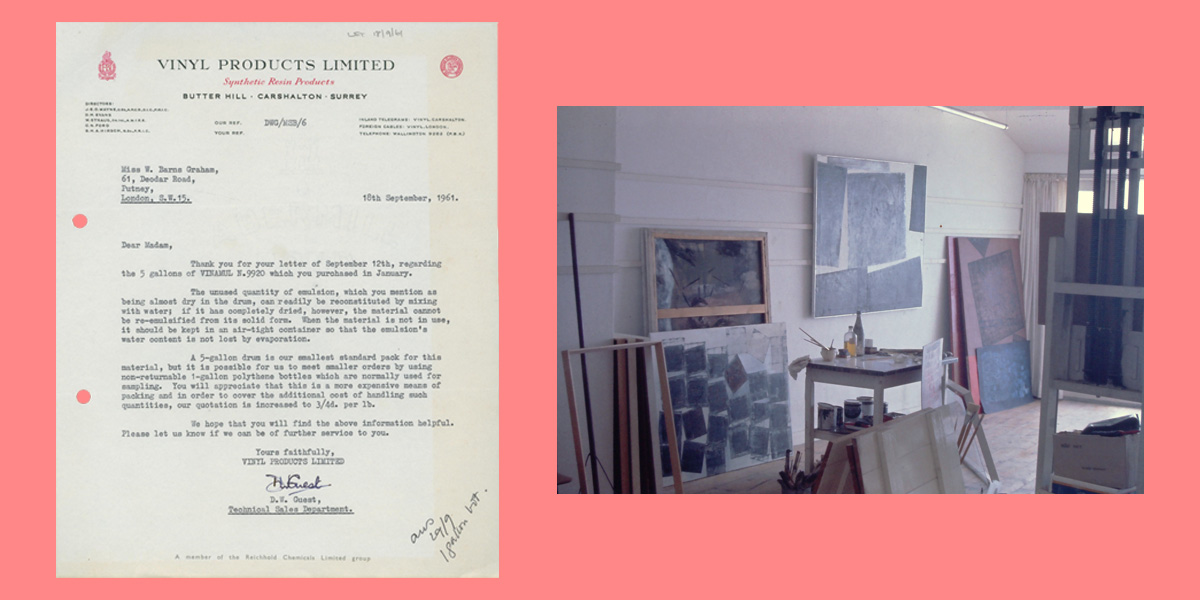

A letter from Vinyl Products Limited, WBG/6/5/1/2/1; photo by Irene Winsby of Barns-Graham's Barnaloft studio c.1964, BGP/3/8/137

Innovation

Barns-Graham’s experimentation with materials is evidenced in archival documents from the 1960s onwards. During cataloguing, an item of note came to light: a letter from Vinyl Products Limited to Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, dated 18 September 1961. This letter may seem of little relevance when compared with other documents concerning the artist’s materials. However, the explicit reference to a 5-gallon purchase of the material Vinamul raises exciting questions, particularly: What was the artist using this for?

Defined as a vinyl acetate copolymer emulsion, Vinamul is still in production and has a wide range of (mainly industrial) uses. Barns-Graham’s uses for this material remain speculative, and to ascertain whether she used this material within her artwork would require technical examination. However, it is known that similar materials, notably polyvinyl acetate (PVA), were used by modernist painters throughout the latter half of the 20th century. Previous and ongoing research into Italian artist Alberto Burri, for example, seeks to establish the artist’s use of PVA as both the priming of the painter’s surface and the medium with which he mixed his pigments.

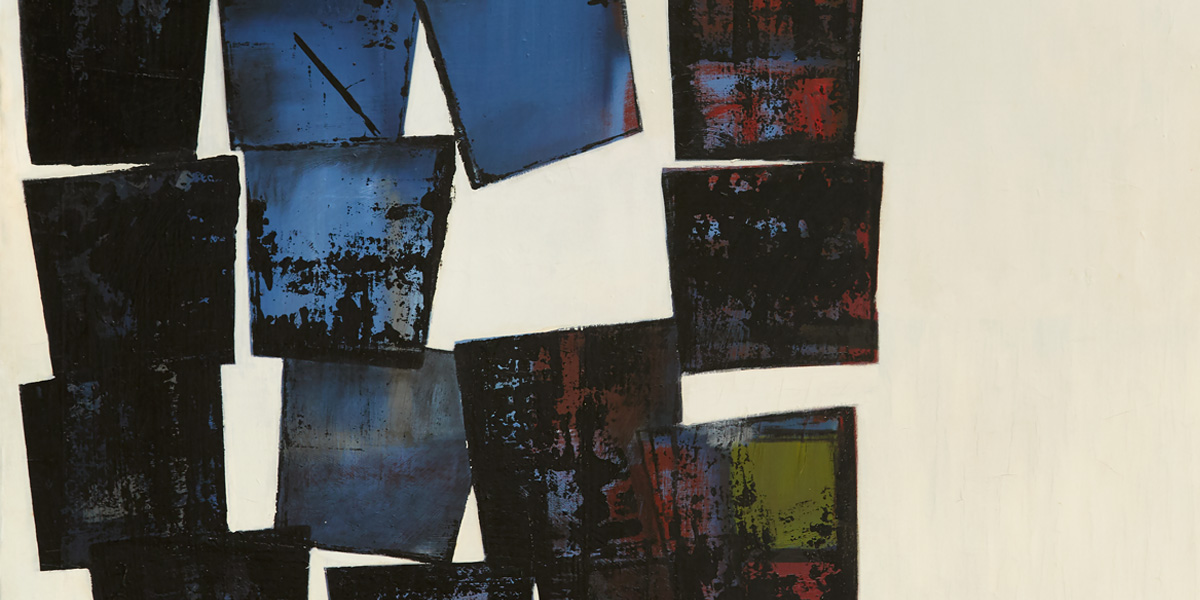

Detail of Buckets, 1959, oil on canvas, BGT472

Barns-Graham’s use of non-conventional household materials is also a matter of debate. For example, it is speculated that she possibly used a white household emulsion in the painting Buckets, 1959. The painting, oil on canvas, features a high gloss black paint, which, from closer examination, sits on the surface of the painting, possibly applied to a previously dried layer. The medium used has resisted the underlying paint, causing a disparate effect across the surface, with noticeable beading.

Effects such as this could arise from the subsequent addition of a water-soluble medium onto a dried, hydrophobic surface, such as oil paint. In addition to this painting, at least two similar works within the WBGT Collection appear to have been created using similar methods and materials; however, these paintings are from a slightly later period.

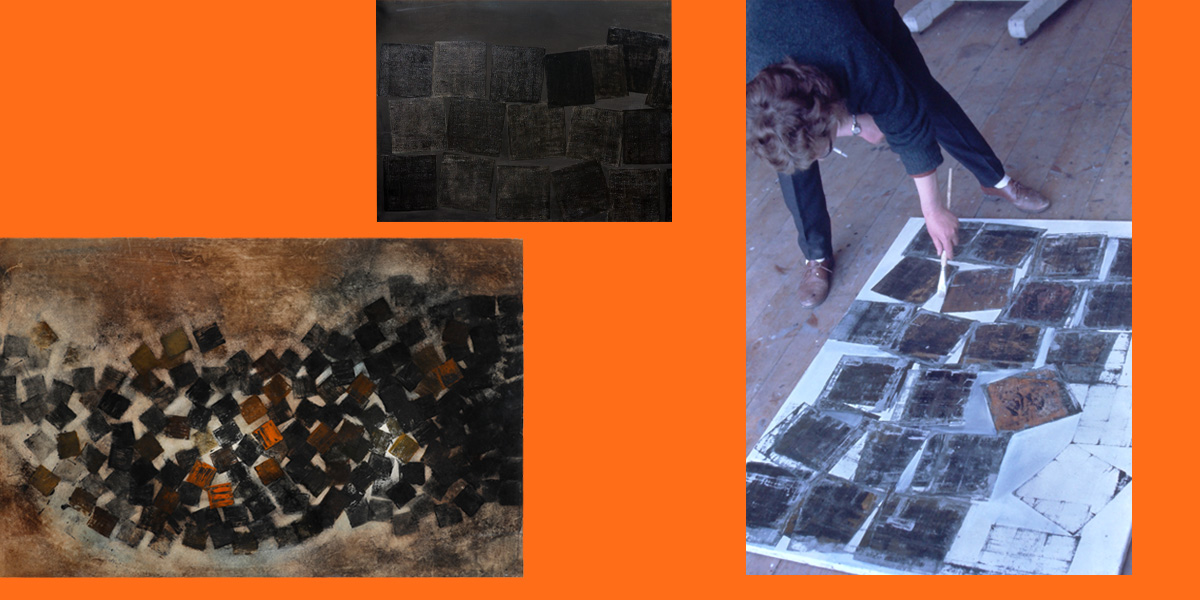

Swarm, 1963, oil on hardboard, BGT552; Untitled, 1963, oil on canvas, BGT439; photo by Irene Winsby of Barns-Graham painting in her Barnaloft Studio, c.1964, BGP/3/8/135

A detailed technical examination of these paintings could be conducted to establish whether Barns-Graham was using Vinamul as a medium. For example, analytical methods such as FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) and Raman Spectroscopy have been previously used to assist in identifying components associated with these materials. These methods could also provide comparative data to the materials available with the WBGT Collection, such as powdered pigments and paint samples.

It is interesting to note that Barns-Graham’s adoption of acrylic paint corresponds to a change in theme, notably, the painting series Things of a Kind in Order and Disorder. This series, described as having its basis within the scientific exploration of painting, explores themes of colour, geometry, and space. These innovative new works, which bear relation to the work of optical painters such as Bridget Riley and Frank Stella, amongst others, hint at an exceptionally experimental approach towards painting. This transmutation of media is indicative of a practice susceptible to continuous change, and its lineage can be traced through Barns-Graham’s practice, notably within the artist’s transition from representation to abstraction in the 1940s.

Rowan James and WBG in the studio at Balmungo, 1983. Photo: Antonia Reeve

Collaboration

When cataloguing materials relating to the ordering of fine art materials, a significant feature of these documents was the involvement of Barns-Graham’s friend and studio manager, Rowan James. With the earliest of these documents dating back to the 1960s, they chart an increasingly collaborative relationship between Barns-Graham and James. From 1973 onward, the year of Rowan James’s employment, they show that Barns-Graham went from having a largely self-sufficient artist practice, whereby the artist managed the day-to-day tasks associated with studio upkeep, to delegating many of these responsibilities to Rowan James. As such, from the year of her employment, James’s name appears with increasing frequency throughout the archival documents.

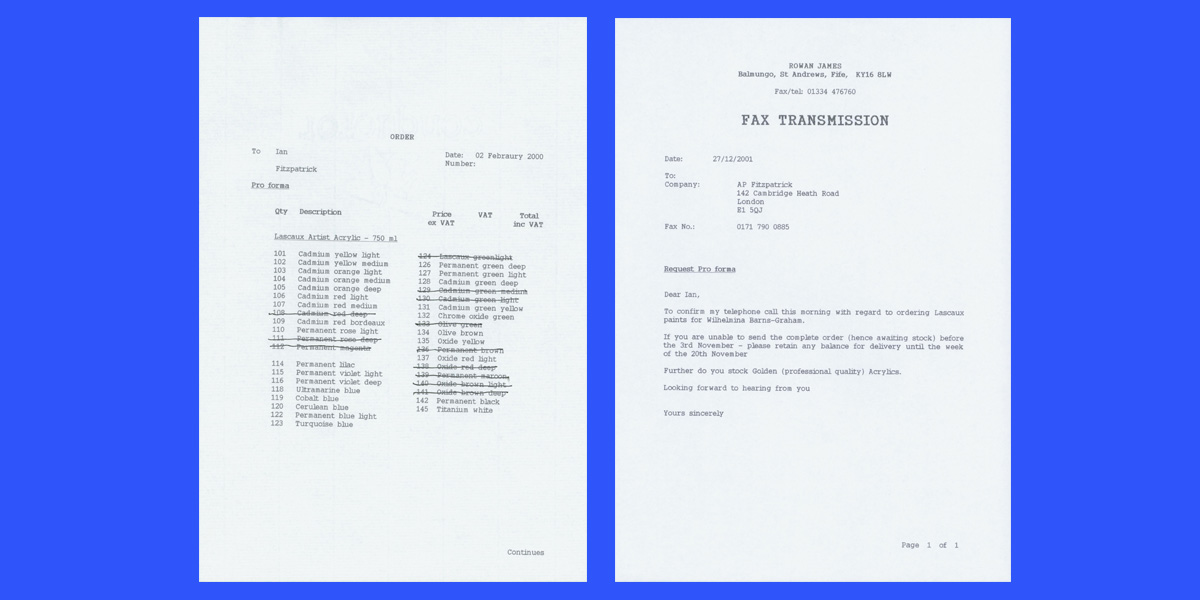

The documents clearly illustrate a feature of James’s role as having included the research and procurement of suitable artist materials. They include order forms, notes, and invoices from a diverse group of suppliers relating to the ordering of fine art materials and framing supplies, and demonstrate there was direct correspondence between James and the suppliers. For example, within documents from the early 2000s, we see James corresponding with the art suppliers, AP Fitzpatrick Fine Art Materials, enquiring about the order of both Lascaux Artist’s Acrylics (paints used within Barns-Graham’s screen-printing practice in collaboration with Graal Press), and Golden Artist Colours, the contemporary successor of Bocour Paints. Both paint brands are represented in Barns-Graham’s archival studio materials.

Two fax transmissions from Rowan James to AP Fitzpatrick, WBG/6/5/1/2/13

Contained within the Archive, we see marketing materials relating to at least nine paint manufacturers and suppliers: Golden Artist Colours, Schmincke, Winsor and Newton, Rowney, Daler and Rowney, Lefranc and Bourgeois, C. Roberson and Co., and Lascaux. Branded materials from these manufacturers include product brochures from colourmen such as C. Roberson and Co, a historic paint manufacturer, whose links date back to the 19th Century, and include associations with historic movements such as the Pre-Raphaelites, and later colour charts from paint manufacturers such as Golden Artist Colours dating to the early 2000s. This document contains physical samples of paint from the manufacturer and may prove to be a useful document for future conservation and technical examination.

Golden Artist Colors Paint Chart, WBG/6/5/2/27

Additionally, there is documented correspondence between James and at least 13 different artist material suppliers. Through this correspondence, Barns-Graham’s continued use of acrylic paint is widely evidenced. For example, within an invoice and order form for Atlantis Art and Conservation Supplies dated 25/05/2001, we are provided with a detailed list of the pigments ordered. The invoice show us that Barns-Graham was still using a significant amount of material in her late career.

Barns-Graham remains an enigmatic figure within contemporary and modern art, and there is a great deal more research to be conducted into her practice, notably the artist’s use of experimental and innovative materials. Through the process of cataloguing these documents, this project has sought to uncover the intricacies and nuances of the artist’s use of materials. Following an exploration of the materials underlying her work, we can ascertain that Barns-Graham championed non-conventional methods of creation and media, whether by her early adoption of acrylic paints, or the professional collaboration underlined by her friendship with Rowan James. In any event, Barns-Graham continues to excite debate and exploration, both of her work and materials, which show an exuberant view of the world through the adoption of colour.

WBG working in her Balmungo studio, 1992, BGP/3/12/12. Photo: Laura Graham

Bibliography

Adam, Robert., & Robertson, Carol. (2003). Screenprinting : the complete water-based system. Thames & Hudson. https://www.thamesandhudsonusa.com/books/screenprinting-the-complete-water-based-system-softcover

Button, V. (2020). Wilhelmina Barns-Graham. Sansom & Company.

De Sá, S. F., Viana, C., & Ferreira, J. L. (2021). Tracing Poly(Vinyl Acetate) Emulsions by Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies: Identification of Spectral Markers. Polymers, 13(21). https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM13213609

Foster, A. (2008). The history and development of acrylics: acrylic paint has a short history, especially when compared to oil and watercolor. For many artists who work in acrylic, having knowledge of the paint’s chemical properties can help them use the medium more effectively. American Artist, 72(793), 8–10. https://go-gale-com.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=00027375&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA187842405&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=fulltext

Green Lynne. (2011). W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life. Lund Humphries Publishers Limited. https://www.lundhumphries.com/products/w-barns-graham-a-studio-life

Izzo, F. C., Balliana, E., Pinton, F., & Zendri, E. (2014). A preliminary study of the composition of commercial oil, acrylic and vinyl paints and their behaviour after accelerated ageing conditions. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage, 14(1), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.6092/ISSN.1973-9494/4753

Jones, F. N., Mao, W., Ziemer, P. D., Xiao, F., Hayes, J., & Golden, M. (2005). Artist paints—an overview and preliminary studies of durability. Progress in Organic Coatings, 52(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PORGCOAT.2004.03.008

Pozzi, F., Arslanoglu, J., Carò, F., & Stringari, C. (2016). Conquering space with matter: a technical study of Alberto Burri’s materials and techniques. Applied Physics A: Materials Science and Processing, 122(10). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00339-016-0435-7

Rogge, C. E., & Epley, B. A. (2023). An Investigation into the Pigments Present on the Late Paintings and Ephemera of Barnett Newman: Context and Correlations. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 62(4), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/01971360.2022.2117770